Just for fun.

Pa at CO Fort St. Vrain nest, 2/17/20

Just for fun.

Pa at CO Fort St. Vrain nest, 2/17/20

EAGLET DAILY PHOTOS AND MILESTONES

© elfruler 2019-2020

Click here for an Introduction to this page.

Photos here are from the 2019 breeding season in a Bald Eagle’s nest in Bluff City, TN, broadcast live by East Tennessee State University, and are used by permission. Click here for link to the live cam. The focus here is on the elder of two eaglets, BC14. Many thanks to Michelle France and Donna Young for helping to collect the screen captures and tell the story.

Measurements are derived or calculated mainly from Bortolotti 1984a, 1984c, and 1984d, and Gerrard and Bortolotti 1988 (Click here for References). Numbers given here are in the ball park but will vary from one eaglet to another. % indicates the proportion a particular measurement bears to its value at the juvenile’s full size (Click here for information about taking measurements.)

BC14 hatched at 10:32 a.m. on 3/11/19. The cam provided a rare bird’s-eye (pun intended) view of how an eaglet uncurls itself from inside the egg in the first few seconds of hatching.

I’ve slowed the stream to 10% of normal speed and added arrows to indicate the back, head, left wing, right wing, beak, tail, legs and feet, egg tooth (yes! the egg tooth!), umbilicus, and receding yolk sac of the hatchling. The eaglet has its back to us and its head is down, tail up.

In the weekly galleries below, click on photos for larger views and to scroll through images. The numbering of Days refers to the age of BC14; Day 0 is Hatch Day, Day 1 is 24 hours after hatch, etc.

The eaglet is hatched with pink skin covered by a thin layer of light gray natal down. The beak and cere are gray, facial skin is dark, legs and feet are pinkish-cream-colored, eye ring is dark and protruding. The eaglet is weak, with limited mobility, balance, and vision. First feeding can occur within about 2 ½ hours.

| HEIGHT | WEIGHT | BEAK LENGTH | FOOT PAD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 |

Skin color changes from pink to bluish-gray, feet and legs are cream-colored; cere turns from pale gray to pale yellow. Steadily gains strength and balance through the week, gaining ability to take food, “swim” on belly with wings and legs, escape from nest cup. Eyes focusing better, seeking out and imprinting on parents. Sibling competition begins. Natal down and egg tooth remain through the week. First PS can occur about 12 hours after first feeding.

| Day 6 |

Skin around eyes becomes lighter gray. Supraorbital ridge more prominent by mid-week. Egg tooth disappears. Cere turns gray, rictus of mouth pale yellow. Feet are beginning to grow rapidly; talons are beige and growing. Second down appears as early as Day 6. Juvenal contour feathers (pin feathers) start to emerge on wings, back, and legs by week’s end; male’s remiges emerge earlier than female’s. (The contour feathers emerge from the natal down follicles and push the natal down out as they grow.) Facial bristle feathers emerging around eyes and beak. Reaching out for food more actively; backing up to nest edge to slice; walking sturdily on hocks; preening, stretching, flapping, and scooting as far out as the nest rails.

| Day 13 |

Growth spurt begins and size differences between male and female develop, especially in weight, beak length, foot pad, and 8th primary feather. Females are larger, but males grow earlier and more quickly. By mid-week, female is gaining 70-180g per day, male 80-150g per day. Beak and feet growing rapidly. Talons turn from beige to black. Second down thickens, approaching ability to thermoregulate. Some second down is growing on the front of the upper region of the tarsometatarsi. Wing primary and covert feathers lengthen, pushing out natal down at the tips; primaries grow a little over 7mm per day. Contour feathers emerge on back, shoulders, legs, and breast. Rectrices start to emerge by mid-week. Beginning to stand on toes briefly. Stretching and rousing, pellet casting, resting on the rails.

| Day 20 | (F 57%, M 61%) |

Growth spurt continues. Remiges are increasingly measurable. Rictus of mouth is yellow. Second down covers entire body except on top of head where natal down layer is still prominent (resulting in that famous “mohawk” look). Head, neck, and side contour feathers coming in. Pecking at food, grasping and playing with nesting materials, wobbly toe-walking by the end of the week. Sibling competition transitions into play.

| Day 27 | M 115mm (87%) | ||||

| Day 27-33 |

Energy demands for metabolism and growth peak by Day 30, then weight gain tapers off. Feet nearly full size by week’s end and are turning yellow. Stretching, flapping, preening, and more confident toe-standing and -walking. Standing on nest twigs as if on a branch, practicing holding with toes and talons. Parents hold food further away to encourage reaching; eaglet may lunge for food and attempt to tear off bites with beak; hasn’t yet mastered the skill of holding food down with feet.

| Day 34 | M 3000g (72%) | M 27mm (87%) | M 129 (98%) | |

| Day 32-38 | M 110-116mm |

At week’s end the eaglet is about 3/4 of full weight. Feet are nearly full grown. Toes and tarsometatarsi fully grown (making banding possible). Legs, feet, lores, and rictus of mouth are yellow. Stretching and flapping, standing securely, grabbing and mantling food as it is delivered, tearing food more effectively. Grasping and playing with nest materials with talons and beak. Vocalizations transitioning from chirps to persistent chittering and loud “squees,” especially at parental visits and food deliveries.

| Day 41 | M 3300g (73%) | M 29mm (90%) | M 130 (98%) | |

| Day 37-43 | M 146-152mm |

From Days 40-45 growth of beak and feet slows; feet and legs will be fully grown by Day 50. Contour feathers on front of the upper region of the tarsometatarsi emerging. Wing flapping becoming more vigorous, flap-hopping higher. Standing on the rails to slice. Long stretches of standing and looking out, or sleeping on the rails.

| Day 48 | M 3500g (88%) | M 30mm (92%) | M 132mm (100%) | |

| Day 42-48 | M 181-187mm |

Contour feathers on sides and belly filling in. Whitish sheaths still visible at bases of remiges and upper- and underwing coverts. Confident standing. More effective self-feeding, but still relies on parents for most feedings; grabbing, stealing, and mantling food. Vigorous flapping, lifting off, enjoying the wind. May begin branching, perhaps with 1-2 flaps, often by stepping.

| Day 55 | M 3700g (92%) | M 30mm (93%) | |

| Day 47-53 | M 217-233mm |

After about Day 60 growth tapers off except beak, hallux claw, and flight feathers. Some remnants of sheaths at bases of wing coverts. Juvenal body feathers nearly complete except on wings and tail; contour feathers on flanks still filling in, as well as on the upper region of the tarsometatarsi. Axillary feathers (wingpits) mostly white. Aggressively grabbing and attempting to steal food from parents and siblings. Flapping results in hovering in mid-air for several seconds. Siblings watch, mimic, and play with each other. Branching likely.

| Day 62 | M 3850g (96%) | M 30mm (94%) | ||

| Day 52-58 | M 253-259mm |

|||

| Day 57-63 | M 288-294mm |

Lower leg feathers are thickening. Aggressive food grabbing, stealing, and mantling. Confident one-foot perching and preening on branches. Vigorous flapping and long hovers. Sometimes stumbles when landing, learning to use wings to regain balance. Fledging is possible from Weeks 10-13. Males usually fledge 3-4 days before females.

| Day 62-68 | M 324-330mm |

Growth of primaries slows after 72 days. Branching more confidently, learning to perch, move around, and use wings for balance on branches. Fledging can occur suddenly and without warning, although eaglet may look intently at nearby branches and appears to evaluate suitable landing spots. First landing is usually awkward, and eaglet may end up on the ground.

| Day 67-73 | M 360-366mm |

By Day 80 primaries have reached 80% and rectrices 84% of their full length (achieved in the second winter). Male primaries growth tapers off, but female primaries continue to grow after fledge. Juvenal feathers will be longer than those of mature adults and will become shorter with each molt until year 5. Beak and hallux talon not yet fully grown at fledge (they will reach full size by the second or third winter).

| Day 80 | M 50mm |

BC14 fledged unintentionally on Day 81, 5/31/19, but the eaglet was ready. The branch on which it was perched broke and the eaglet fell but quickly recovered and flew strongly in the direction of trees across the creek.

The new fledgling juvenile eagle returned to the nest 3 days later and visited several times before dispersing from the area for good. Its sibling, BC15, fledged 8 days after BC14.

PERSONAL NOTE: In my opinion the 2 eaglets at this nest in 2019 are of the same gender, either female-female or male-male (it is impossible to know which). The younger may appear to be slightly smaller, but according to Bortolotti (1986a, 1986b), a younger sibling is almost always slightly smaller than an elder of the same gender. A male develops earlier and more quickly, but a female eventually is noticeably larger, especially so if she is the elder. (Male-female broods are quite rare.) It is quite difficult to ascertain relative size because of the camera angle and lack of perspective, but at fledge I could not see a significant size difference between BC14 and BC15.

EAGLET GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

© elfruler 2019

The growth and development of a Bald Eaglet from hatch to fledge takes about 10-13 weeks. Along a spectrum of morphological and behavioral states from least developed (“altricial“) to most developed (“precocial“), raptors fall near the minimally developed end. Altricial hatchlings have few or no feathers, closed eyes, little to no mobility, no ability to thermoregulate, and need parental care to survive and grow. Precocial hatchlings have a full layer of down feathers, open eyes, mobility and thermoregulating ability, ability to feed themselves, and are soon able to leave the nest. Raptors are considered “semi-altricial”: at hatch they have a thin layer of down but are unable to thermoregulate, their eyes are open or partly open although not yet able to focus or follow movements, they have some mobility, and they are entirely dependent on parents to survive and grow.

Thanks to the work of Gary Bortolotti and Jon M. Gerrard in Saskatchewan in the 1970s and 1980s, we have reliable information on the development of eagle nestlings from hatch to fledge, including weight and growth of the critical beak, feet, and wing feathers. (Click here for References.) Beak and feet grow faster than other body parts because they are essential tools for survival and take several weeks to be fully developed. The “gangly” and “clownish” look of young eaglets is largely due to the disproportionate growth of feet and beaks.

Hatched with thin natal down, eaglets gain a thicker second set of down starting a week or so after hatching, and soon thereafter their body (contour) feathers begin to grow. These feathers will become the juvenal (first-year) eagle’s smooth covering by the time it fledges. They take several weeks to reach full length, especially the wing feathers which are not yet fully grown until after fledge.

Steadily emerging behaviors reflect the growth of the eaglet’s skeleton, muscles, feathers, and neurological systems. As the days go by the eaglet develops the ability to hold up its head, maintain its balance, focus on and follow the parents with its eyes, reach out and eventually lunge for food from the parent’s beak and finally pull bites of food off a fish by itself. Especially with the emergence of contour feathers, an eaglet engages in near constant preening, using its beak to remove the protective sheaths around the feathers and help the vanes unfurl and its barbs lock together.

It swiftly gains mobility, from pulling itself by its wings and pushing with its legs through the soft nest materials, to standing and walking on its hocks, stepping backwards toward the edge of the nest and tipping up onto its toes to expel wastes over the side, ultimately graduating to standing tall on its toes and walking around like its parents.

As wing feathers begin to grow the eaglet waves its arms and extends them overhead in a full body stretch (which falconers call “warbling”), then builds its breast muscles with vigorous flapping, flap-hopping, and finally catching the air to hover above the nest. Inbetween all this activity, an eaglet spends many hours sleeping and resting, apparently doing nothing but growing.

The pages here follow the daily growth and development of the two eaglets at the Bluff City nest in Tennessee in 2019, through an online camera operated by East Tennessee State University (ETSU). BC14 hatched on 11 March at 10:32 a.m., and BC15 hatched a day and a half later, 12 March by about 11:00 p.m. Photos and videos here are from the Bluff City cam and are used by permission.

Heartfelt thanks to Michelle France, camera operator and keen observer at the ETSU nests, and to my long-time eagle-watching partner Donna Young for her careful observations of Bald Eagle behavior and eaglet development over the years, and her contributions to the descriptions on these pages.

MEASURING ADULT, SUBADULT, AND JUVENILE BALD EAGLES

©elfruler 2018

See MEASURING AN EAGLE for details on procedures and challenges of acquiring measurements and descriptions and figures of the features measured. General References are given at this link, while References specific to each table below are given at the end of each table.

The charts below give measurements of adult and subadult Bald Eagles as reported in peer-reviewed publications. I have omitted measurements that are questionable or not standard. (If a reader knows of reports that I do not include here, please contact me with details.)

These numbers provide some context for consideration of several factors relating to size in Bald Eagles:

The age of a Bald Eagle during its first five years affects several measurements.

ADULT BALD EAGLE MEASUREMENTS TABLE

MEASURING AN EAGLE: REFERENCES

Baird, S.F., T.M. Brewer, and R. Ridgway 1874. A History of North American Birds: Volume III, Land Birds. Little, Brown, and Co.: Boston.

Baldwin, S. P., H. C. Oberholser, and L.G. Worley 1931. Measurements of Birds (1931). Scientific Publications of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Cleveland, OH.

Bent, A.C. 1937. Life histories of North American birds of prey: order falconiformes. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Bortolotti, G.R. 1984a. Criteria for determining age and sex of nestling Bald Eagles. Journal of Field Ornithology 55: 467-481.

Bortolotti, G.R. 1984c. Sexual size dimorphism and age-related size variation in Bald Eagles. The Journal of Wildlife Management 48: 72-81.

Bortolotti, G.R. 1984d. Physical development of nestling Bald Eagles with emphasis on the timing of growth events. The Wilson Bulletin 96: 524-542.

Broley, C.L. 1947. Migration and nesting of Florida Bald Eagles. The Wilson Bulletin. 59: 3-20.

Chura, N.J., and P.A. Stewart 1967. Care, food consumption, and behavior of Bald Eagles used in DDT tests. The Wilson Bulletin. 79: 441-448.

Fitzpatrick, B.M. and J.R. Dunk 1999. Ecogeographic variation in morphology of Red-Tailed hawks in western North America. Journal of Raptor Research 33: 305-312.

Friedmann, H. 1950. The birds of North and Middle America: A descriptive catalog. Part XI. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Gerrard, J.M. and G.R. Bortolotti 1988. The Bald Eagles: Haunts and Habits of a Wilderness Monarch. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London.

Gerrard, J.M., A.R. Harmata, and P.N. Gerrard 1992. Home range and activity of a pair of Bald Eagles breeding in northern Saskatchewan. Journal of Raptor Research 26: 229-234.

Imler, R.H. and E.R. Kalmbach 1955. The Bald Eagle and its economic status. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Circular 30.

Maestrelli, J.R. and S.N. Wiemeyer 1975. Breeding Bald Eagles in captivity. The Wilson Bulletin 87: 45-53.

Meiri, S. and T. Dayan 2003. On the validity of Bergmann’s rule. Journal of Biogeography 30: 331-351.

Palmer, R.S., ed. 1988. Handbook of North American Birds vol. 4: Family Cathartidae, New World condors and vultures; Family Accipitridae (first part), Osprey, kites, bald eagle and allies, accipiters, harrier, buteo allies. Yale University Press, New Haven and London: 187-237.

Salewski, V. and C. Watt 2016. Bergmann’s rule: a biophysiological rule examined in birds. Oikos 126: 161-172.

Southern, W.E. 1964. Additional observations on winter Bald Eagle populations: including remarks on biotelemetry techniques and immature plumages. The Wilson Bulletin 64: 121-137.

Stalmaster, M. The Bald Eagle. Universe Books, New York.

Temple, S.A. 1972. Systematics and evolution of the North American merlins. Auk 89: 325-338.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Forensic Laboratory. The Feather Atlas: Flight feathers of North American birds.

Whaley, W.H. and C.M. White 1994. Trends in geographic variation of Cooper’s hawk and Northern goshawk in Northern America: a multivariate analysis. Proceedings of the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology 5: 161-209.

Wright, B.S. 1953. The relation of Bald Eagles to breeding ducks in New Brunswick. The Journal of Wildlife Management 17: 55-62.

MEASURING AN EAGLE

©elfruler 2018

Acquiring accurate measurements of a bird is a tricky business, and it turns out that there are relatively few peer-reviewed publications that report measurements for Bald Eagles. In the pages that follow I present tabulations of the credible numbers of which I am aware. I begin with some general information on measurements and measuring. General References are given at this link.

The most reliable measurements are taken from a live, wild, healthy eagle, but capturing one is difficult and rarely attempted. Some researchers have used captive eagles, recently deceased eagles, and museum specimens for measurements, but these present some issues that must be considered:

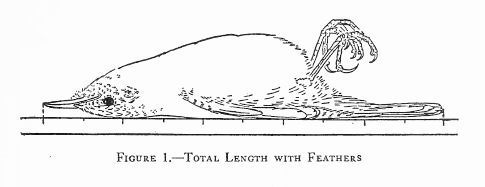

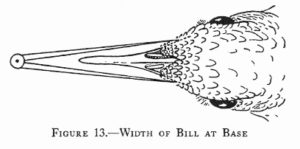

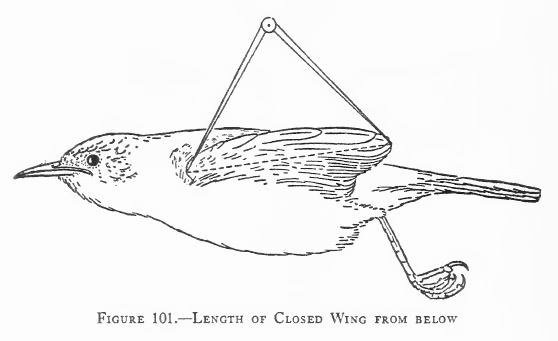

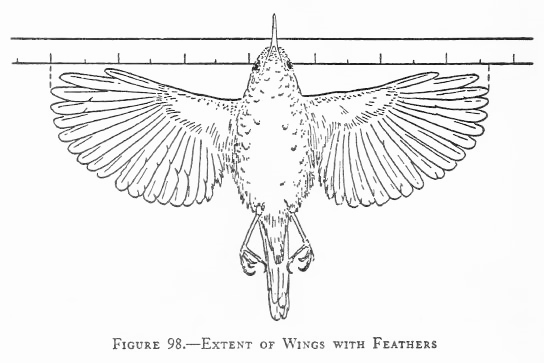

P. Baldwin, H. C. Oberholser, and L.G. Worley, Measurements of Birds (1931) established a comprehensive and standardized system of obtaining linear measurements of the various parts of birds, which continues to guide researchers. It includes detailed discussion of procedures and challenges and the tools needed to obtain accurate and consistent measurements, along with drawings showing what to measure, how to position the bird, and where to place the tools.

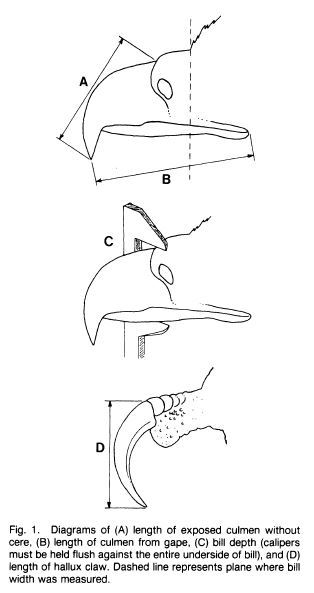

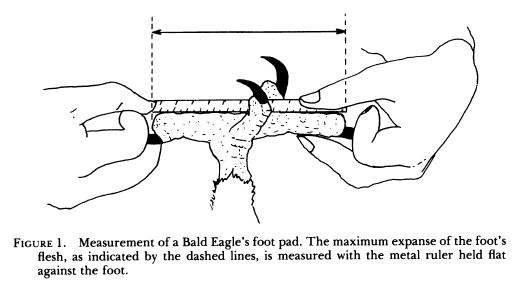

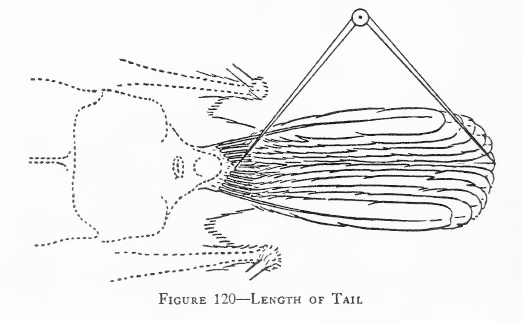

The following measurements of Bald Eagles have been reported in published literature. (Figures from Baldwin et al. 1931 are used under the license agreement with Creative Commons. Figures from Bortolotti 1984a are used with permission of The Journal of Field Ornithology. Figures from Bortolotti 1984c are used with permission of The Wildlife Society, Bethesda, MD.)

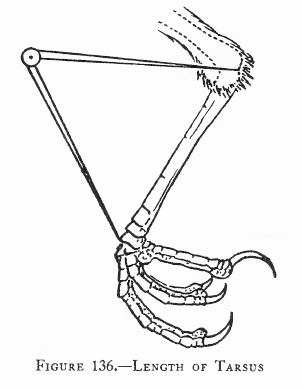

This measurement is a long diagonal from the intratarsal joint at the back of the leg to the base of the toe at the front of the foot. Reports of this measurement can vary, perhaps because of imprecision of identifying the end points. (Figure 136 (© Baldwin et al. 1931 as licensed by Creative Commons).

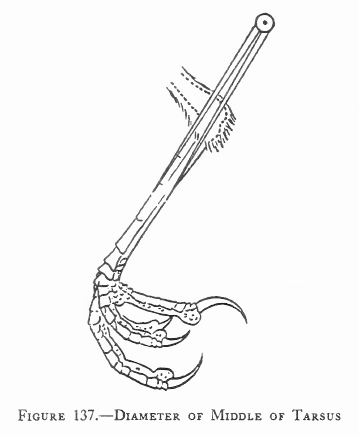

This measurement is a long diagonal from the intratarsal joint at the back of the leg to the base of the toe at the front of the foot. Reports of this measurement can vary, perhaps because of imprecision of identifying the end points. (Figure 136 (© Baldwin et al. 1931 as licensed by Creative Commons). The tarsus is wider when measured from front to back and narrower when measured from one side to the other; generally the front-to-back diameter of the tarsus is measured (Fig. 137 © Baldwin et al. 1931 as licensed by Creative Commons). But the few reported measurements for Bald Eagles are taken just above the toes at the narrowest point of the tarsus, and calculations are of an average of two measurements taken front-to-back and side-to-side, yielding mean width rather than diameter. Either way, width is a highly variable measurement in reports, and specimens do not always yield reliable readings (Bortolotti 1984a and Bortolotti 1984c).

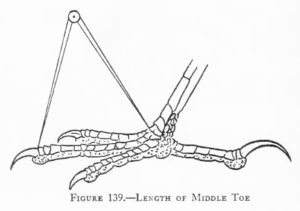

The tarsus is wider when measured from front to back and narrower when measured from one side to the other; generally the front-to-back diameter of the tarsus is measured (Fig. 137 © Baldwin et al. 1931 as licensed by Creative Commons). But the few reported measurements for Bald Eagles are taken just above the toes at the narrowest point of the tarsus, and calculations are of an average of two measurements taken front-to-back and side-to-side, yielding mean width rather than diameter. Either way, width is a highly variable measurement in reports, and specimens do not always yield reliable readings (Bortolotti 1984a and Bortolotti 1984c). from its base at the metatarsal joint outward to the end of the toe, not including the talon (Fig. 139 © Baldwin et al. 1931 as licensed by Creative Commons).The toe must be extended as straight as possible.

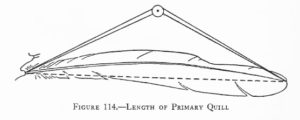

from its base at the metatarsal joint outward to the end of the toe, not including the talon (Fig. 139 © Baldwin et al. 1931 as licensed by Creative Commons).The toe must be extended as straight as possible. the skin to its tip, without flattening the shaft (Fig. 114 © Baldwin et al. 1931 as licensed by Creative Commons).

the skin to its tip, without flattening the shaft (Fig. 114 © Baldwin et al. 1931 as licensed by Creative Commons).

MEASURING ADULT, SUBADULT, AND JUVENILE BALD EAGLES

ADULT BALD EAGLE MEASUREMENTS TABLE

You must be logged in to post a comment.